“There is no plan B” was the mantra of the climate activists and politicians who gathered in Copenhagen in December 2009 to hammer out a new agreement to limit carbon emissions. They were wrong. There is a plan B and this book describes it.

Although often called a ‘sceptic’ the appellation does not really apply to Bjorn Lomborg. He doesn’t dispute that global warming is real and is caused by humans. What he does question is the assumption that reducing CO2 emissions is the best or only way of dealing with its effects.

The author set up the “Copenhagen Consensus” which brought together a group of eminent economists to examine ways in which, with a limited amount of money, it would be possible to do most good to most people. The top three were: control of HIV/AIDS, providing micronutrients to tackle malnutrition and trade liberalisation. The last of these three has the double benefit of providing agriculturalists in the developing world with higher incomes and lower food costs to people in the developed world. The three options relating to CO2 emissions came in last.

He also suggests that the benefits of reducing CO2, even if Kyoto had achieved its targets, would have been minimal and delayed the effects of global warming in 2100 by only a few years

His book starts with the iconic polar bears. He points out that in the few areas where bear populations are falling most of the reduction is due to hunting. Other topics he covers and his assertions include:

• Heat deaths. More people die of cold in winter than die of heat in summer. Global warming would reduce weather related deaths.

• Rising sea levels. The rate of rise predicted by the IPCC is not markedly higher than the rise observed during the past century and better sea defences are a cheaper solution. He accepts that the gates designed to protect London from flooding have indeed been closed more frequently in recent years but points out that this was to keep water in during low flow periods not to keep it out during floods.

• Water stress. In most of the world, the increase in rainfall will more than compensate for the extra evaporation caused by higher temperatures.

• Tropical storms. Whilst there had been an apparent increase in storms as monitored by satellites over the last 30 years, longer term data shows no upward trend. The storm which flooded New Orleans did so because of inadequate flood defences not because it was an extraordinary storm.

• Malaria. This is not a disease limited to hot countries, one of the worst epidemics was in Russia in the 1920s, and increased temperature will not necessarily lead to an increase.

In each of these cases, and others that he examines, he compares the costs of a targeted response to the cost of controlling CO2 emissions. However what he compares is the low cost of each specific solution to the total cost of reducing CO2. This is false. The cost of reducing CO2 will be shared between all the problems that will be alleviated by CO2 reduction. Whether adopting this approach would have changed his conclusions is a moot point but he should have examined it.

Despite this reservation I recommend this book.

Ron

Publisher: : Marshall Cavendish (2007)

ISBN 978-0-462-09912-5

Sunday 10 January 2010

Saturday 9 January 2010

Book Review: Christopher Booker - The Global Warming Disaster

Christopher Booker is a columnist for the Telegraph (right of centre, highbrow). If there is a thread to his columns it is railing against abuses of authority and the resulting impact on individuals or (mostly small) businesses. If the authority stems from the EU then his invective steps up a gear. He is also the co-author of “Scared to Death” which looks at exaggerated scares, mainly but not always in the medical field (SARS, CJD/BSE, listeria, the Millennium bug, etc). A chapter of this book was entitled “Saving the Planet: Global Warming – the New Secular Religion.”

As he describes it himself he got interested in global warming via Nimbyism (NIMBY = Not in my Back Yard). He got involved in protests against a wind turbine near his home and from that started looking at the need for renewable energy sources and threat of global warming.

The book moves chronologically from cooling worries of the 1960s, past Hansen’s appearance before a sweltering Senate committee, via the successful legal challenge to Gore’s “Inconvenient Truth”, on to the recent cooling and the run-up to Copenhagen. One disadvantage of a chronological approach is that events which are logically consecutive get split up between chapters. So we get Mann and the Hockey-stick and the McIntyre and McKitrick challenge in chapter 4, Gore’s use of the Hockey-stick in his book and the Wegman report on it in chapter 6 and papers to support the Hockey-stick in chapter 7.

He also demonstrates a lack of altruism in some of the major players. Gore has invested heavily in alternative energy ventures and even offset his high carbon footprint by paying money to a company in which he has an interest. Maurice Strong, who was closely involved in setting up the UNEP and the IPCC, was implicated in the Iraq ‘money-for-food’ scandal and now has a major role in the multi-billion dollars carbon credits business. (Booker has recently returned to this theme in his newspaper pointing out the many business deals of Dr Rajendra Pachauri, head of the IPCC.)

It is commonplace to accuse “deniers” of being in cahoots with the energy industry. What this book shows is that money is also an important motivator among the ”warmists”.

In one sense the book is prophetic. It was written before the CRU emails and details the lack of independence of many of the leading climate scientists behind the IPCC reports. It was also written before COP15 in Copenhagen and identifies the problems of getting China and other developing countries on board for any binding international agreement.

If, like the author, you believe that the real “global warming disaster” is the vast amount of money being diverted to fight a chimera then this book will give you more ammunition. On the other hand, if believe that the effects of global warming are real and dangerous this book will do little to convince you otherwise.

Ron

Publisher: Continuum

ISBN: 9781441110527

As he describes it himself he got interested in global warming via Nimbyism (NIMBY = Not in my Back Yard). He got involved in protests against a wind turbine near his home and from that started looking at the need for renewable energy sources and threat of global warming.

The book moves chronologically from cooling worries of the 1960s, past Hansen’s appearance before a sweltering Senate committee, via the successful legal challenge to Gore’s “Inconvenient Truth”, on to the recent cooling and the run-up to Copenhagen. One disadvantage of a chronological approach is that events which are logically consecutive get split up between chapters. So we get Mann and the Hockey-stick and the McIntyre and McKitrick challenge in chapter 4, Gore’s use of the Hockey-stick in his book and the Wegman report on it in chapter 6 and papers to support the Hockey-stick in chapter 7.

He also demonstrates a lack of altruism in some of the major players. Gore has invested heavily in alternative energy ventures and even offset his high carbon footprint by paying money to a company in which he has an interest. Maurice Strong, who was closely involved in setting up the UNEP and the IPCC, was implicated in the Iraq ‘money-for-food’ scandal and now has a major role in the multi-billion dollars carbon credits business. (Booker has recently returned to this theme in his newspaper pointing out the many business deals of Dr Rajendra Pachauri, head of the IPCC.)

It is commonplace to accuse “deniers” of being in cahoots with the energy industry. What this book shows is that money is also an important motivator among the ”warmists”.

In one sense the book is prophetic. It was written before the CRU emails and details the lack of independence of many of the leading climate scientists behind the IPCC reports. It was also written before COP15 in Copenhagen and identifies the problems of getting China and other developing countries on board for any binding international agreement.

If, like the author, you believe that the real “global warming disaster” is the vast amount of money being diverted to fight a chimera then this book will give you more ammunition. On the other hand, if believe that the effects of global warming are real and dangerous this book will do little to convince you otherwise.

Ron

Publisher: Continuum

ISBN: 9781441110527

Book Review: Ian Plimer, "Heaven and Earth – global warming: the missing science"

I wish I could recommend this book, I really do. After all a book which gives an overview of climate change from the creation of the Earth up to the present, which cites 2311 (mainly peer reviewed) references and runs to over 500 pages can’t be all bad. Can it?

Ian Plimer is both a distinguished geology professor and practicing geologist. As such he takes a long-term view of climate (billions of years not just decades or centuries). During this period earth has undergone changes to climate which make the changes recorded during historical time seem puny by comparison. His background also leads him to consider, and give more weight to, ‘geological’ forcing of climate change such as submarine vents.

The ‘meat’ of the book comes in five chapters headed “The Sun”, “Earth”, “Ice”, “Water” and “Air”. In the “Sun” chapter he argues that the sun as the sole source of external energy is the main driver of climate on earth and that the the interaction of the solar wind with cosmic rays is an important mechanism for climate change. The “earth” chapter covers volcanoes and Milankovitch cycles. He argues that that glaciers and sea ice have always advanced and retreated and that current changes are not unusual. He also discusses the physics of water and the influence some its properties (like the fact that ice floats on water) have on climate. In the “Air” chapter he examines the accuracy of temperature and CO2 measurement. Throughout the book he adopts an undeniably sceptical point view with regard to climate change. That said, he also appears to agree with some of the ‘consensus’ view. For example after saying that water vapour is the main greenhouse gas he continues “When times are warmer, water vapour evaporates more readily.” Later he also writes “Water vapour is an amplifier not a trigger.” He also concedes that “some of the increase in atmospheric CO2 measured over the last 150 years is of human origin.”

I learnt much from this book and many of the questions he raises are valid. For example he quotes from a number of studies which suggest that the residence time of CO2 in the atmosphere is around 5 years, much less that 50 to 200 years assumed by the IPCC.

So why don’t I feel able to recommend it? Well the answer, indirectly, comes from the author himself. In his introduction he says “Hypotheses are invalidated by just one item of contrary evidence, no matter how much confirming evidence is present.” The same could be set of a technical book. If it has errors then the reader cannot rely on it. That, unfortunately is the case with this book.

He says, for example, with reference to devastation of Hurricane Katrina, “The whole of the Texas Gulf area is subsiding. In the three years before the flood ... the city and the surrounding area had undergone rapid subsistence of about one metre.“ He gives no reference for this but later in the book cites a Nature paper (Dixon et al, 2006) which quotes a maximum rate of 28.6 mm/year but that is only at a few isolated spots in New Orleans and its surrounds. In other places nearby the subsidence is much less. He also claims that volcanoes produce more CO2 than fossil fuel burning whereas it is generally accepted than the ratio is 30 to 1 in opposite direction.

The author will often scrupulously cite references for relatively minor statements and then make sweeping statements without any source. In a rather confusing section, where mixes percent and absolute values, he says that 186 billion tons of CO2 enters the atmosphere of which 3.3% [equivalent to 6 billion tons, the accepted figure is 5 times higher] comes from human sources and ... 71 billion tons is exhaled by animals (including humans). This could do with a reference. Later in the same paragraph he says that Global warming did not cause the mass extinction in 65 Ma, and does give a reference.

In a similar way the author has a lot of graphs none of which are referenced and a least one of which is wrongly labelled. In the introduction he admits that they were “fly scratchings” which someone else converted into line diagrams for him so that lack of references is not surprising.

The book could also do with a good editor. Statements like “The winter of 1815-1816 was known as ‘the year without a summer’” should not have been allowed to stand. There are also numerous unnecessary repetitions. For example in one place he writes “...rebound is occurring in Scandinavia, Scotland and Canada after ice sheets up to 5 km thick melted over the last 14,000 years”. Two pages later we read “...ice sheets started to melt 14,700 years ago, and Scandinavia, Scotland and North America are currently rising...”.

The book was warmly welcomed by sceptics and attacked by warmists. There is indeed a lot of ammunition for sceptics but the errors and other shortcomings make the book easy prey for those who want to criticise it. If a second edition is published with the defects corrected it will be a useful contribution to the debate on global warming. Unless, and until, this is done I cannot recommend it.

Ron

Publisher: Quartet

ISBN: 9780704371668

Ian Plimer is both a distinguished geology professor and practicing geologist. As such he takes a long-term view of climate (billions of years not just decades or centuries). During this period earth has undergone changes to climate which make the changes recorded during historical time seem puny by comparison. His background also leads him to consider, and give more weight to, ‘geological’ forcing of climate change such as submarine vents.

The ‘meat’ of the book comes in five chapters headed “The Sun”, “Earth”, “Ice”, “Water” and “Air”. In the “Sun” chapter he argues that the sun as the sole source of external energy is the main driver of climate on earth and that the the interaction of the solar wind with cosmic rays is an important mechanism for climate change. The “earth” chapter covers volcanoes and Milankovitch cycles. He argues that that glaciers and sea ice have always advanced and retreated and that current changes are not unusual. He also discusses the physics of water and the influence some its properties (like the fact that ice floats on water) have on climate. In the “Air” chapter he examines the accuracy of temperature and CO2 measurement. Throughout the book he adopts an undeniably sceptical point view with regard to climate change. That said, he also appears to agree with some of the ‘consensus’ view. For example after saying that water vapour is the main greenhouse gas he continues “When times are warmer, water vapour evaporates more readily.” Later he also writes “Water vapour is an amplifier not a trigger.” He also concedes that “some of the increase in atmospheric CO2 measured over the last 150 years is of human origin.”

I learnt much from this book and many of the questions he raises are valid. For example he quotes from a number of studies which suggest that the residence time of CO2 in the atmosphere is around 5 years, much less that 50 to 200 years assumed by the IPCC.

So why don’t I feel able to recommend it? Well the answer, indirectly, comes from the author himself. In his introduction he says “Hypotheses are invalidated by just one item of contrary evidence, no matter how much confirming evidence is present.” The same could be set of a technical book. If it has errors then the reader cannot rely on it. That, unfortunately is the case with this book.

He says, for example, with reference to devastation of Hurricane Katrina, “The whole of the Texas Gulf area is subsiding. In the three years before the flood ... the city and the surrounding area had undergone rapid subsistence of about one metre.“ He gives no reference for this but later in the book cites a Nature paper (Dixon et al, 2006) which quotes a maximum rate of 28.6 mm/year but that is only at a few isolated spots in New Orleans and its surrounds. In other places nearby the subsidence is much less. He also claims that volcanoes produce more CO2 than fossil fuel burning whereas it is generally accepted than the ratio is 30 to 1 in opposite direction.

The author will often scrupulously cite references for relatively minor statements and then make sweeping statements without any source. In a rather confusing section, where mixes percent and absolute values, he says that 186 billion tons of CO2 enters the atmosphere of which 3.3% [equivalent to 6 billion tons, the accepted figure is 5 times higher] comes from human sources and ... 71 billion tons is exhaled by animals (including humans). This could do with a reference. Later in the same paragraph he says that Global warming did not cause the mass extinction in 65 Ma, and does give a reference.

In a similar way the author has a lot of graphs none of which are referenced and a least one of which is wrongly labelled. In the introduction he admits that they were “fly scratchings” which someone else converted into line diagrams for him so that lack of references is not surprising.

The book could also do with a good editor. Statements like “The winter of 1815-1816 was known as ‘the year without a summer’” should not have been allowed to stand. There are also numerous unnecessary repetitions. For example in one place he writes “...rebound is occurring in Scandinavia, Scotland and Canada after ice sheets up to 5 km thick melted over the last 14,000 years”. Two pages later we read “...ice sheets started to melt 14,700 years ago, and Scandinavia, Scotland and North America are currently rising...”.

The book was warmly welcomed by sceptics and attacked by warmists. There is indeed a lot of ammunition for sceptics but the errors and other shortcomings make the book easy prey for those who want to criticise it. If a second edition is published with the defects corrected it will be a useful contribution to the debate on global warming. Unless, and until, this is done I cannot recommend it.

Ron

Publisher: Quartet

ISBN: 9780704371668

Book Review: Fred Pearce, "The Last Generation: how nature will take her revenge for climate change"

Right from the start I had mixed feelings about this book. Fred Pearce is a science writer who I respect. Recently he published an article pointing out that there are reasons other than the risk of climate change for cutting back on the use of fossil fuels, citing their use for the production of artificial fertilisers. This corresponds to my own view which is that fossil fuels are a finite resource, at some point in the future they will inevitably be exhausted and the sooner we start to plan our transition the smoother it is likely to be. Also a few years ago he published a longish article in New Scientist based on some of my work which has prejudiced me in his favour.

On the other hand I believe that books with cover (front and back) pictures of a city engulfed in flames and alarmist titles like “The Last Generation” are counterproductive. Particularly when the only review quoted on the front cover reads “This is the most frightening book that I have ever read.” (Eat your heart out Stephen King.) So how did I resolve my conflicts?

The book is, literally, wide ranging. Polar research stations, Brazilian rain forests, the Sahara, Indonesian peat bogs, Siberian permafrost and glaciers in the four corners of the earth: all are part of the climatic picture he presents. In many cases the author has been to the parts of the world he is talking about: when he has not he has still managed to talk face-to-face with most of the scientists involved.

The science is accurately covered but not always without bias. He is too kind to Michael Mann and his Hockey-stick. The book was of course written before the release of the CRU emails but the Wegman report, which he does not mention, should have alerted him to the fact that other papers from a small group of authors which also produce ‘hockey-sticks’ could not be considered as independent confirmation.

Anybody who has studied climate change can be forgiving for thinking of it as a gradual process. The sedate dance of the earth and sun which follows the Milankovitch cycles of 20,000, 40,000 and 100,000 years. The 1,500 cycle which is so gentle that some people doubt its existence. The 11 year sunspot cycle which occasionally produced a diminuendo but always follows it by a gentle crescendo. What this book does is to show that this is not the case; that large changes in temperature, falls and rises, can come about in periods measured in decades rather than centuries or millennia.

Some of these changes are well attested, the Dansgaard-Oeschger events for example. Temperature estimates from Greenland ice cores these show that temperature can rise 2 to 10 C in a decade, remain there for a century or so and then fall. Others are more speculative. It is known that the warming from the last ice age was interrupted and the earth’s temperature dropped again for more than 1,000 years. The widely accepted reason for this is that vast quantities of dammed up melt water flowed suddenly into the north Atlantic and interrupted the circulation of the oceans. Some scientists speculate that melting caused by global warming could have a similar effect.

Whilst it alright for Stephen King to generate tension among his readers by hinting at vaguely defined dangers it does not go well with a scientific explanation of climate change. The author recognises this and is open about the fact that even when the speed and magnitude of the changes to climate are well supported by scientific evidence there is little agreement on what caused them. He says “After many generations of experiencing global climate stability, human society seems in imminent danger of returning to a world of crazy jumps. ...There is still a chance that the jumps won’t materialise... but the chances are against it.”

Whilst those who are already firmly convinced that global warming is a serious and imminent threat will find new arguments in this book many dyed-in-the-wool sceptics will remain unconvinced. I work with a wide variety of scientists from many different disciplines and nothing annoys them more than phrases such as “the science is settled”; they know from their own experience that science rarely achieves that degree of absolute certainty. A book like this which describes the science accurately and is honest about the uncertainties is more likely to convince open minded sceptics than one which only presents one apocalyptic side of the story.

So, Fred Pearce has retained my respect. But what about the title. Well, in the chapter on “Conclusions” he back-tracks a bit. He explains that he did not mean the title to imply that we would be last generation ever to live, only that we would be the last generation to live with certainty of a stable climate. I suspect that the publisher believed, rightly unfortunately, that an accurate title such as “Climate instability: a balanced review of the possibilities and uncertainties” would not sell.

Ron

Eden Project Books

ISBN: 9781903919880

On the other hand I believe that books with cover (front and back) pictures of a city engulfed in flames and alarmist titles like “The Last Generation” are counterproductive. Particularly when the only review quoted on the front cover reads “This is the most frightening book that I have ever read.” (Eat your heart out Stephen King.) So how did I resolve my conflicts?

The book is, literally, wide ranging. Polar research stations, Brazilian rain forests, the Sahara, Indonesian peat bogs, Siberian permafrost and glaciers in the four corners of the earth: all are part of the climatic picture he presents. In many cases the author has been to the parts of the world he is talking about: when he has not he has still managed to talk face-to-face with most of the scientists involved.

The science is accurately covered but not always without bias. He is too kind to Michael Mann and his Hockey-stick. The book was of course written before the release of the CRU emails but the Wegman report, which he does not mention, should have alerted him to the fact that other papers from a small group of authors which also produce ‘hockey-sticks’ could not be considered as independent confirmation.

Anybody who has studied climate change can be forgiving for thinking of it as a gradual process. The sedate dance of the earth and sun which follows the Milankovitch cycles of 20,000, 40,000 and 100,000 years. The 1,500 cycle which is so gentle that some people doubt its existence. The 11 year sunspot cycle which occasionally produced a diminuendo but always follows it by a gentle crescendo. What this book does is to show that this is not the case; that large changes in temperature, falls and rises, can come about in periods measured in decades rather than centuries or millennia.

Some of these changes are well attested, the Dansgaard-Oeschger events for example. Temperature estimates from Greenland ice cores these show that temperature can rise 2 to 10 C in a decade, remain there for a century or so and then fall. Others are more speculative. It is known that the warming from the last ice age was interrupted and the earth’s temperature dropped again for more than 1,000 years. The widely accepted reason for this is that vast quantities of dammed up melt water flowed suddenly into the north Atlantic and interrupted the circulation of the oceans. Some scientists speculate that melting caused by global warming could have a similar effect.

Whilst it alright for Stephen King to generate tension among his readers by hinting at vaguely defined dangers it does not go well with a scientific explanation of climate change. The author recognises this and is open about the fact that even when the speed and magnitude of the changes to climate are well supported by scientific evidence there is little agreement on what caused them. He says “After many generations of experiencing global climate stability, human society seems in imminent danger of returning to a world of crazy jumps. ...There is still a chance that the jumps won’t materialise... but the chances are against it.”

Whilst those who are already firmly convinced that global warming is a serious and imminent threat will find new arguments in this book many dyed-in-the-wool sceptics will remain unconvinced. I work with a wide variety of scientists from many different disciplines and nothing annoys them more than phrases such as “the science is settled”; they know from their own experience that science rarely achieves that degree of absolute certainty. A book like this which describes the science accurately and is honest about the uncertainties is more likely to convince open minded sceptics than one which only presents one apocalyptic side of the story.

So, Fred Pearce has retained my respect. But what about the title. Well, in the chapter on “Conclusions” he back-tracks a bit. He explains that he did not mean the title to imply that we would be last generation ever to live, only that we would be the last generation to live with certainty of a stable climate. I suspect that the publisher believed, rightly unfortunately, that an accurate title such as “Climate instability: a balanced review of the possibilities and uncertainties” would not sell.

Ron

Eden Project Books

ISBN: 9781903919880

Book Review: Mike Hulme, "Why we disagree about climate change: Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity".

Whether you believe that tackling climate change is the biggest threat to our planet, or whether you think it is all a con to squeeze more taxes out of a gullible public, the reasons you put forward for holding your views are not the real ones. You hold to your views because it suits you. That, in a nutshell, is the thesis of Mike Hulme. He would probably (in fact, more than probably) be horrified that I have summarised it in this way so let me expand on it.

The opinions we hold on a particular issue are determined by a matrix of complementary perceptions. How do we view science? What do we value? What beliefs do we hold? What do we fear? How do we want to be governed? The stand we take on climate change is shaped by our response to these different questions and helps to explain, for example, why global warming is generally viewed differently by the political left and the political right. The factors, which lead us to reach a decision on a political issue, are same ones as lead us to decide on all the other issues we have to face. This, as I am sure Mike Hulme would acknowledge, applies to author himself. As well as being a Professor at the School of Environmental Sciences of the University of East Anglia he is a committed Christian and many of his analogies have a biblical origin.

Hulme takes us through the questions I have listed above, and many others. For example in the section on risk he introduce two pairs of risk types. One of these pairs is situated/un-situated risk. Situated risk is when someone wants to build a waste incineration plant at the bottom of your garden; un-situated risk is the danger that the output from incineration plants all over the world will be dangerous. He second pair is affective/analytic. Affective risk is one you can actually experience, fumes from the incineration plant; analytic risk is one you only know about indirectly, published figures on the output of noxious gases from incinerations plants.

Climate change naturally falls into the category of ‘un-situated’ and ‘analytic’ risks. A lot of the effort of climate change campaigners has been to move the argument to ‘situated’ and ‘affected’ risks. Polar bears stranded on an ice floe far from safety are a ‘situated’ risk. Similarly, claiming that a large number of extreme weather events are caused by climate change increases the number of people for whom climate change becomes and ‘affective’ risk.

Given that Mike Hulme is a professor at the University of East Anglia, one of the world’s main centres for climate change research, the book is fairly balanced; in this he is being consistent with past statements where he has expressed worries that extreme language is having a negative effect on reactions to climate change. He also tackles one of the great taboo subjects in relation to climate change: population. After all total carbon dioxide emission can be considered as per capita consumption times population so why should all the effort be on the one (per capita consumption) not the other. China claims to have reduced its population growth by 300 million people as a result of its ‘one child’ policy. This, even at China’s relatively low per capita use, is equivalent to more that 5% of all carbon emissions and much more effective that Kyoto.

Despite this there are still few areas where his bias shows. In discussing participatory democracy he mentions the realclimate.org blog but not the more popular (although sceptical) wattusupwiththat.org. He quotes Eric Hobsbawm, the ‘British historian’, as saying, “Democracy, however desirable, is not an effective device for solving global or transnational problems.” What he fails to mention is that Hobsbawm is a life-long communist and once described Stalinist communism as a ‘worthwhile experiment’.

The last chapter, Beyond Climate Change, is in some ways the most intriguing. He introduces four ‘myths’ about climate change; the word myth is used in the anthropological sense of a deeply significant narrative about assumed truths. These are:

• Lamenting Eden – a search for an irenic state which existed before the fall,

• Presaging apocalypse - which sits well with eschatological calls to ‘repent as the end of the world is nigh’,

• Constructing Babel – referring to the attempt to build a city with a ‘tower that reaches to the heavens’ and signifying a desire to supplant God by human mastery of the universe,

• Celebrating Jubilee – based on the Jewish idea that every 50 years, soil, slaves and debtors should be liberated and humanity could make a fresh start.

Behind all these narratives is the pessimistic concept of a ‘wicked problem’; one which defies ‘rational and optimal’ solutions. As Hulme points out the world is now very much aware of the concept and threat of climate change but in reality little has been done. He suggests that climate change may be such a ‘wicked problem’.

Bjorn Lomborg is quoted three times in the book, always accurately and never in a disparaging way. As far as I can tell Lomborg is the only sceptic referenced in the book (though in one sense Lomborg is not a sceptic – he does not dispute climate change but only the much touted responses to it.) Could it be that Mike Hulme, a High Priest of climate change with privileged access to its inner sanctum, hold views not very dissimilar from those of “The Sceptical Environmentalist”? I doubt it but, as I said, the last chapter is intriguing.

I recommend this book.

Ron

Publisher: Cambridge University Press

ISBN: 9780521898690

The opinions we hold on a particular issue are determined by a matrix of complementary perceptions. How do we view science? What do we value? What beliefs do we hold? What do we fear? How do we want to be governed? The stand we take on climate change is shaped by our response to these different questions and helps to explain, for example, why global warming is generally viewed differently by the political left and the political right. The factors, which lead us to reach a decision on a political issue, are same ones as lead us to decide on all the other issues we have to face. This, as I am sure Mike Hulme would acknowledge, applies to author himself. As well as being a Professor at the School of Environmental Sciences of the University of East Anglia he is a committed Christian and many of his analogies have a biblical origin.

Hulme takes us through the questions I have listed above, and many others. For example in the section on risk he introduce two pairs of risk types. One of these pairs is situated/un-situated risk. Situated risk is when someone wants to build a waste incineration plant at the bottom of your garden; un-situated risk is the danger that the output from incineration plants all over the world will be dangerous. He second pair is affective/analytic. Affective risk is one you can actually experience, fumes from the incineration plant; analytic risk is one you only know about indirectly, published figures on the output of noxious gases from incinerations plants.

Climate change naturally falls into the category of ‘un-situated’ and ‘analytic’ risks. A lot of the effort of climate change campaigners has been to move the argument to ‘situated’ and ‘affected’ risks. Polar bears stranded on an ice floe far from safety are a ‘situated’ risk. Similarly, claiming that a large number of extreme weather events are caused by climate change increases the number of people for whom climate change becomes and ‘affective’ risk.

Given that Mike Hulme is a professor at the University of East Anglia, one of the world’s main centres for climate change research, the book is fairly balanced; in this he is being consistent with past statements where he has expressed worries that extreme language is having a negative effect on reactions to climate change. He also tackles one of the great taboo subjects in relation to climate change: population. After all total carbon dioxide emission can be considered as per capita consumption times population so why should all the effort be on the one (per capita consumption) not the other. China claims to have reduced its population growth by 300 million people as a result of its ‘one child’ policy. This, even at China’s relatively low per capita use, is equivalent to more that 5% of all carbon emissions and much more effective that Kyoto.

Despite this there are still few areas where his bias shows. In discussing participatory democracy he mentions the realclimate.org blog but not the more popular (although sceptical) wattusupwiththat.org. He quotes Eric Hobsbawm, the ‘British historian’, as saying, “Democracy, however desirable, is not an effective device for solving global or transnational problems.” What he fails to mention is that Hobsbawm is a life-long communist and once described Stalinist communism as a ‘worthwhile experiment’.

The last chapter, Beyond Climate Change, is in some ways the most intriguing. He introduces four ‘myths’ about climate change; the word myth is used in the anthropological sense of a deeply significant narrative about assumed truths. These are:

• Lamenting Eden – a search for an irenic state which existed before the fall,

• Presaging apocalypse - which sits well with eschatological calls to ‘repent as the end of the world is nigh’,

• Constructing Babel – referring to the attempt to build a city with a ‘tower that reaches to the heavens’ and signifying a desire to supplant God by human mastery of the universe,

• Celebrating Jubilee – based on the Jewish idea that every 50 years, soil, slaves and debtors should be liberated and humanity could make a fresh start.

Behind all these narratives is the pessimistic concept of a ‘wicked problem’; one which defies ‘rational and optimal’ solutions. As Hulme points out the world is now very much aware of the concept and threat of climate change but in reality little has been done. He suggests that climate change may be such a ‘wicked problem’.

Bjorn Lomborg is quoted three times in the book, always accurately and never in a disparaging way. As far as I can tell Lomborg is the only sceptic referenced in the book (though in one sense Lomborg is not a sceptic – he does not dispute climate change but only the much touted responses to it.) Could it be that Mike Hulme, a High Priest of climate change with privileged access to its inner sanctum, hold views not very dissimilar from those of “The Sceptical Environmentalist”? I doubt it but, as I said, the last chapter is intriguing.

I recommend this book.

Ron

Publisher: Cambridge University Press

ISBN: 9780521898690

Peer Review

Peer review is the process publishers of scientific journals use to ensure that the papers they publish are of an acceptable standard. Basically when they receive a paper for publication they send it off to a small group of people who have already published papers in the same field, the ‘peers’ of the author, for an opinion. If it is favourable they publish it; if not they reject it.

Much of the discussion around the leaked emails from the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia focussed on the peer review process. It appeared that some climate change scientists tried hard to stop sceptical papers being published or, if they had been published, from appearing in IPCC reports. At the same time these very climate scientists were citing an absence of critical peer reviewed papers as evidence that the scientific consensus accepted the concept of global warming.

One of the factors behind this was clearly shown in the Wegman report into the validity of the temperature “Hockey-stick” which showed that many papers on paleoclimatology were published by a relatively small group who co-authored papers with each other.

It is clearly not in the interest of Science (with a capital S) that valid criticisms should be suppressed; but also it is not in the interest of the reputation of a journal that it publishes below standard papers. Journals should have a clearly stated policy on the standards they expect for publication: awareness and understanding of the work of other experts, a clear statement of the advances or differences relative to other published work, a description of the data and analytical methods used. Provided that a paper meets these criteria it should get published.

Whilst it is relevant for a journal to identify the areas of research in which it is seeking papers it is invidious for it to identify what ‘line’ it takes. For example the British Royal Society on its web site has a statement showing that it clearly accepts that climate change is caused by people. This is wrong. It is of course perfectly reasonable for distinguished Fellows of the Royal Society to hold views on climate change, to express these views and even to write The Times with the letters FRS after their names. But, no matter how many of the Fellows hold a particular view it should never become the view of the society itself.

Often the reason that critics use the blogosphere is their comments relate to (sometimes blatant) flaws in the original paper. Journals are understandably reluctant to publish such criticism as it reveals flaws in their review process. (For a humorous take on this see: http://www.scribd.com/doc/18773744/How-to-Publish-a-Scientific-Comment-in-1-2-3-Easy-Steps)

An egregious example was the use of inverted sediment data. A paper (Mann et al, Proxy-based reconstructions of hemispheric and global surface temperature variations over the past two millennia, PNAS, 2008) was recently published on the assumption that extra lake sediment was indicative of increased temperature (whereas the converse is true). What is more in this case the amount of sediment had been artificially increased in recent years by nearby road building and agricultural work so any conclusions would have been false. To expect a sceptic to produce a paper for peer review reworking the misleading data is obviously not justified.

A related, but also important aspect of testing the validity of published papers concerns the release of data. In the past a scientist would do an experiment and report the results in a journal. Other scientists would try to replicate the result. If they got the same result, the findings of the initial experiment would be confirmed; if not, they would be rejected. In the case of climate science ‘the experiment’ consists of collecting, processing and analysing data. The hard work is in the collection and processing of the data; the interesting work is in the analysis. This, might for example, mean travelling around remote parts of Siberia drilling holes in tree rings, carefully preserving the samples and analysing them later in a laboratory to quantify growth rates as a proxy for temperature. It is therefore understandable that after doing all the hard work scientists would be reluctant to give their data away to all and sundry who could enjoy analysing them. It’s a bit like asking a ‘traditional’ scientist if you can come round and work in the laboratory that was used for the initial experiment.

On the other hand in most cases the cost of collecting the data came from the public purse so whilst the original worker might feel they have intellectual ownership of the data in reality it should be in the public domain.

We believe that data should be made available at the time of publication but accept that it is reasonable to make a small charge (similar to that made for copies of article to non-subscribers of a journal), to require a clear statement of why the data are needed and an acknowledgement of the source in any subsequent publication.

Much of the discussion around the leaked emails from the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia focussed on the peer review process. It appeared that some climate change scientists tried hard to stop sceptical papers being published or, if they had been published, from appearing in IPCC reports. At the same time these very climate scientists were citing an absence of critical peer reviewed papers as evidence that the scientific consensus accepted the concept of global warming.

One of the factors behind this was clearly shown in the Wegman report into the validity of the temperature “Hockey-stick” which showed that many papers on paleoclimatology were published by a relatively small group who co-authored papers with each other.

It is clearly not in the interest of Science (with a capital S) that valid criticisms should be suppressed; but also it is not in the interest of the reputation of a journal that it publishes below standard papers. Journals should have a clearly stated policy on the standards they expect for publication: awareness and understanding of the work of other experts, a clear statement of the advances or differences relative to other published work, a description of the data and analytical methods used. Provided that a paper meets these criteria it should get published.

Whilst it is relevant for a journal to identify the areas of research in which it is seeking papers it is invidious for it to identify what ‘line’ it takes. For example the British Royal Society on its web site has a statement showing that it clearly accepts that climate change is caused by people. This is wrong. It is of course perfectly reasonable for distinguished Fellows of the Royal Society to hold views on climate change, to express these views and even to write The Times with the letters FRS after their names. But, no matter how many of the Fellows hold a particular view it should never become the view of the society itself.

Often the reason that critics use the blogosphere is their comments relate to (sometimes blatant) flaws in the original paper. Journals are understandably reluctant to publish such criticism as it reveals flaws in their review process. (For a humorous take on this see: http://www.scribd.com/doc/18773744/How-to-Publish-a-Scientific-Comment-in-1-2-3-Easy-Steps)

An egregious example was the use of inverted sediment data. A paper (Mann et al, Proxy-based reconstructions of hemispheric and global surface temperature variations over the past two millennia, PNAS, 2008) was recently published on the assumption that extra lake sediment was indicative of increased temperature (whereas the converse is true). What is more in this case the amount of sediment had been artificially increased in recent years by nearby road building and agricultural work so any conclusions would have been false. To expect a sceptic to produce a paper for peer review reworking the misleading data is obviously not justified.

A related, but also important aspect of testing the validity of published papers concerns the release of data. In the past a scientist would do an experiment and report the results in a journal. Other scientists would try to replicate the result. If they got the same result, the findings of the initial experiment would be confirmed; if not, they would be rejected. In the case of climate science ‘the experiment’ consists of collecting, processing and analysing data. The hard work is in the collection and processing of the data; the interesting work is in the analysis. This, might for example, mean travelling around remote parts of Siberia drilling holes in tree rings, carefully preserving the samples and analysing them later in a laboratory to quantify growth rates as a proxy for temperature. It is therefore understandable that after doing all the hard work scientists would be reluctant to give their data away to all and sundry who could enjoy analysing them. It’s a bit like asking a ‘traditional’ scientist if you can come round and work in the laboratory that was used for the initial experiment.

On the other hand in most cases the cost of collecting the data came from the public purse so whilst the original worker might feel they have intellectual ownership of the data in reality it should be in the public domain.

We believe that data should be made available at the time of publication but accept that it is reasonable to make a small charge (similar to that made for copies of article to non-subscribers of a journal), to require a clear statement of why the data are needed and an acknowledgement of the source in any subsequent publication.

Opinions?

We have been planning to add an opinion page to our site for some time but little did we think we would have anything as exciting as the CRU emails and files to discuss. (If you have found this page you probably know what we’re talking about. In case you don’t, CRU stands for the Climatic Research Unit at the University of East Anglia in the UK. It produces one of world’s main climate data sets (in conjunction with the British Met Office) and several prominent climate researchers work there. In late November 2009 more than 1000 emails to and from researchers at the centre were released on the Internet together with several files of data, programs and notes. It is not clear whether it was work of a hacker or a whistle-blower (whichever it was the emails and files were carefully chosen).

Initial reaction was highly polarised. Many sceptical bloggers reacted with glee; this was the smoking gun, which proved that climate change was a hoax/conspiracy. On the other hand realclimate.org, which represents the views of many climate modellers, took the line that the emails revealed nothing other than robust scientific discussion.

After a slight lull the news of the emails became a big story in the mainstream media, in part because they were released a few weeks before the Copenhagen conference to agree a successor to the Kyoto protocol. This was followed by responses from the CRU and IPCC. The professor who figured in many of the emails stood down while an enquiry instituted by the university was carried out. The IPCC also announced an enquiry. Many of the emails dealt with the temperature record produced by the CRU and the university announced that the data set would be reworked over the next three years and as much as possible of the data put into the public domain. As this decision is the most significant change to come about as the result of the emails it is the one we concentrate on here. There are 5 main temperature data sets. Three of them, the one from CRU and two from the USA, use observed temperature readings, and start in the mid-19th century. The other two use data from satellite data and start in 1979. All five are in broad agreement for their common period.

The use of observed data has two main problems. Firstly the records are not continuous; stations close or are moved and new stations open. A symptom of this is that the number of stations available for analysis varies over time reaching a peak between 1970 to 1990 and then declined. Secondly urban development in the vicinity of a met station can make its reading unrepresentative of the surrounding area. Other changes are subtler. From about 1870 onwards thermometers were housed in a standard Stephenson screen, which had whitewashed wooded slats. The whitewash came to be replaced by different paints, which changes the reflectivity of the station. More recent automatic instruments have different housings. Another change is that temperature measurements at sea went over from using water temperature based on a bucket dipped into the sea to using the temperature of the cooling water intake.

We have two concerns about the new data set to be created.

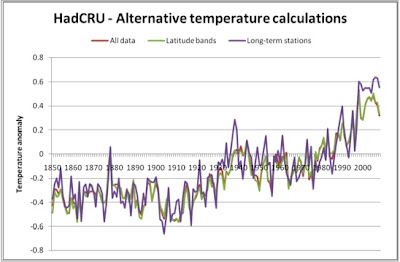

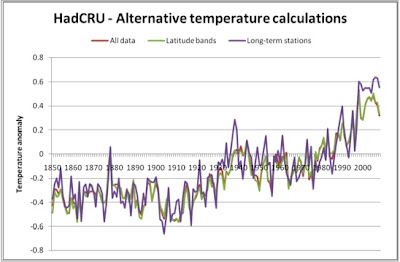

The first is the concept of a single temperature series. In combining data from many sources a number of assumptions, about how to treat missing data for example, have to be made. Often it is not possible to demonstrate that one set of assumptions is better than another. In the right-hand sidebar we show three temperature series we have calculated ourselves using 5º gridded data from the HadCRUt3v series (Figure below).

The first (red) data set using all the data is the same as the published HadCRU series. Temperature depends very heavily on latitude so for the second series we assumed that any grid filled represented temperature at the latitude (green line); this gives equal weight to each latitude band regardless of how many grids had data. The third alternative we examined was to use only grids, which had data for 90% or more of the time (blue). As can be seen there is not much difference between the first two series but third has some important differences. In particular the peak around 1940 is more pronounced as is the more recent temperature increase. We believe that several new series should be published with the assumptions behind each of clearly stated.

Secondly there is a worry that those developing the new series of measured data will ‘know what the answer should be’. For example the emails revealed there was some concern about the temperature peak in the mid 1940s; although not stated in the emails this was because climate models did not represent that peak. There might be a temptation to choose the data and the stations to fit the models.

For the new data to represent a real advance on previous data sets there is also need for some experimental work. One ‘experiment’ could be to set up a series of met stations with different types of Stephenson screens and different types of modern automatic sensors to see what differences, if any, there are. Another could be to set up a series of stations in urban and rural areas (or select carefully chosen stations currently in use) to develop a way of quantifying the urban heat island effect. Nighttime satellite images have already been used to identify urbanised areas; this could be taken a stage further to develop relationships between degree of urbanisation and temperature anomaly. A third experiment could be to measure sea temperature in different ways. Complicating all these experiments is a need to give good global coverage and to apply current findings to past climate records.

Initial reaction was highly polarised. Many sceptical bloggers reacted with glee; this was the smoking gun, which proved that climate change was a hoax/conspiracy. On the other hand realclimate.org, which represents the views of many climate modellers, took the line that the emails revealed nothing other than robust scientific discussion.

After a slight lull the news of the emails became a big story in the mainstream media, in part because they were released a few weeks before the Copenhagen conference to agree a successor to the Kyoto protocol. This was followed by responses from the CRU and IPCC. The professor who figured in many of the emails stood down while an enquiry instituted by the university was carried out. The IPCC also announced an enquiry. Many of the emails dealt with the temperature record produced by the CRU and the university announced that the data set would be reworked over the next three years and as much as possible of the data put into the public domain. As this decision is the most significant change to come about as the result of the emails it is the one we concentrate on here. There are 5 main temperature data sets. Three of them, the one from CRU and two from the USA, use observed temperature readings, and start in the mid-19th century. The other two use data from satellite data and start in 1979. All five are in broad agreement for their common period.

The use of observed data has two main problems. Firstly the records are not continuous; stations close or are moved and new stations open. A symptom of this is that the number of stations available for analysis varies over time reaching a peak between 1970 to 1990 and then declined. Secondly urban development in the vicinity of a met station can make its reading unrepresentative of the surrounding area. Other changes are subtler. From about 1870 onwards thermometers were housed in a standard Stephenson screen, which had whitewashed wooded slats. The whitewash came to be replaced by different paints, which changes the reflectivity of the station. More recent automatic instruments have different housings. Another change is that temperature measurements at sea went over from using water temperature based on a bucket dipped into the sea to using the temperature of the cooling water intake.

We have two concerns about the new data set to be created.

The first is the concept of a single temperature series. In combining data from many sources a number of assumptions, about how to treat missing data for example, have to be made. Often it is not possible to demonstrate that one set of assumptions is better than another. In the right-hand sidebar we show three temperature series we have calculated ourselves using 5º gridded data from the HadCRUt3v series (Figure below).

The first (red) data set using all the data is the same as the published HadCRU series. Temperature depends very heavily on latitude so for the second series we assumed that any grid filled represented temperature at the latitude (green line); this gives equal weight to each latitude band regardless of how many grids had data. The third alternative we examined was to use only grids, which had data for 90% or more of the time (blue). As can be seen there is not much difference between the first two series but third has some important differences. In particular the peak around 1940 is more pronounced as is the more recent temperature increase. We believe that several new series should be published with the assumptions behind each of clearly stated.

Secondly there is a worry that those developing the new series of measured data will ‘know what the answer should be’. For example the emails revealed there was some concern about the temperature peak in the mid 1940s; although not stated in the emails this was because climate models did not represent that peak. There might be a temptation to choose the data and the stations to fit the models.

For the new data to represent a real advance on previous data sets there is also need for some experimental work. One ‘experiment’ could be to set up a series of met stations with different types of Stephenson screens and different types of modern automatic sensors to see what differences, if any, there are. Another could be to set up a series of stations in urban and rural areas (or select carefully chosen stations currently in use) to develop a way of quantifying the urban heat island effect. Nighttime satellite images have already been used to identify urbanised areas; this could be taken a stage further to develop relationships between degree of urbanisation and temperature anomaly. A third experiment could be to measure sea temperature in different ways. Complicating all these experiments is a need to give good global coverage and to apply current findings to past climate records.

Welcome

Please use this blog to discuss anything in relation to the climate change data shown on our site. We very much look forward to your input.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)